Status Anxiety Fuels Exotic Pet Trade

Image JfJacobsz

Lynn Johnson

3 July, 2020

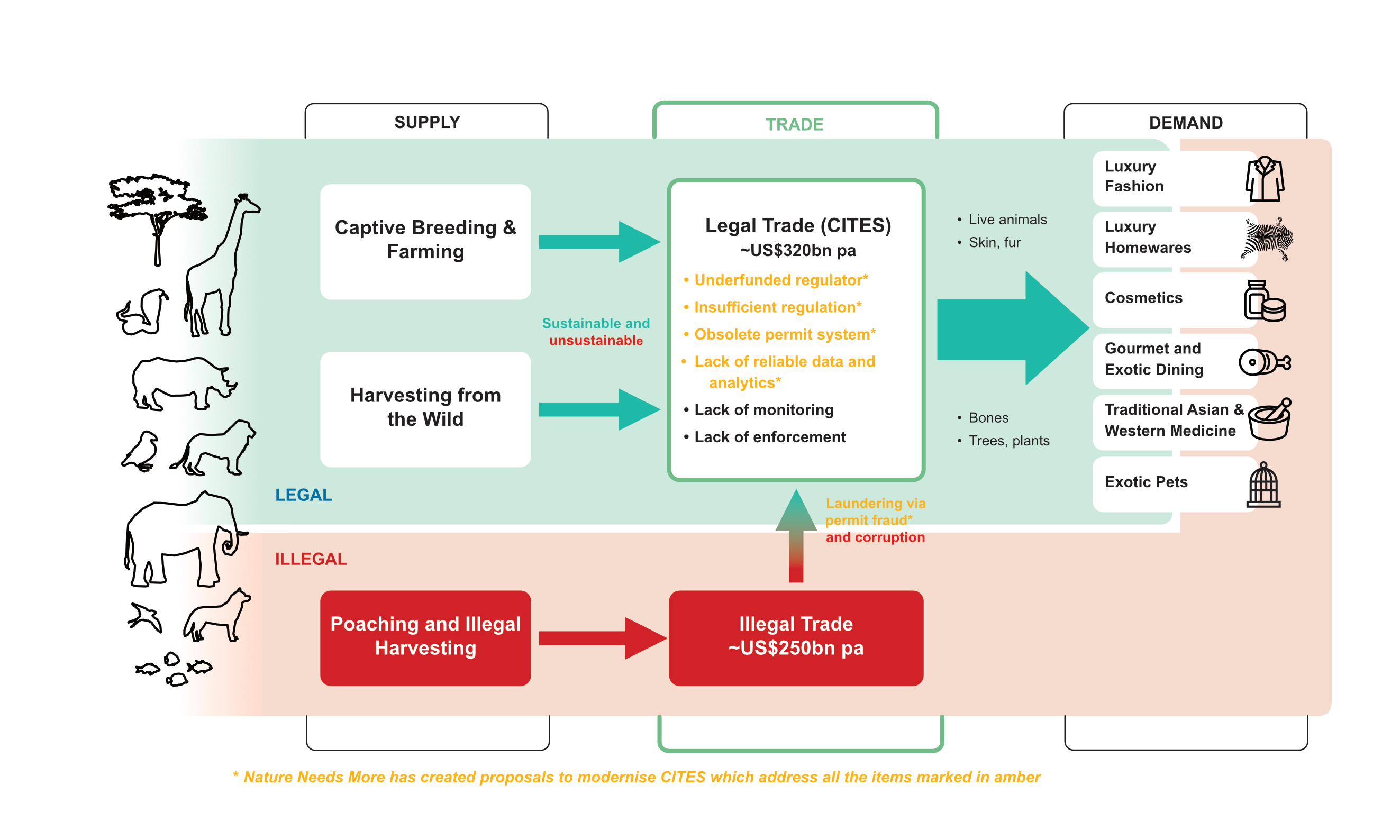

The exotic pet trade is a vast and global industry, with massive numbers of birds, reptiles, amphibians, fish and mammals being bought and sold in stores, markets and online. In too many cases it is hard to distinguish the legal from illegal. The legal trade’s supply chains remain stubbornly opaque while companies try to promote their sustainability credentials. Greenwashing is rife, with glossy PR brochures promoting ethical business models while at the same time companies lobby governments for business exemptions from Freedom of Information laws, claiming the need to protect commercial information.

Be it legal or illegal, what is most desired and most valuable are ‘status’ pets – rare parrots, snakes, turtles and big cats like cheetahs; and the trade is growing. The ease of online purchasing together with the addiction to exotic pet selfies and videos means the ‘status’ pet is now also often an impulse buy. So how can this lucrative and often cruel trade be reined in? After all, direct exploitation for trade has been confirmed as the second biggest factor driving the extinction crisis.

Empathy for the plight of exotic and endangered species is not the way to go. Consumer research shows people in the market for an exotic pet cannot be dissuaded from their purchase by being educated about the species being threatened by trade or knowing the animals are likely to suffer at all stages of the supply chain. Those surveyed for research published in 2016 said “Even if the animals were endangered or were going to suffer while being caught and transported, they’d buy them anyway”.

The key finding in 2016 was that informing perspective owners about the zoonotic disease risks associated with exotic pets could reduce consumer demand by up to 40%; well I bet that is higher now!

Over recent years, most conservation organisations have acknowledged the key to behaviour change in the wildlife trade is to understand the end consumer. Anyone working in marketing, advertising and sales in a commercial space knows this; if you don’t invest in understanding the motivations of consumers it is harder to drive up sales. Still it is almost impossible to find anything on customer segmentation and motivations to buy in the endless reports produced by conservation agencies. But if you don’t know what motivates someone to buy, it is harder to understand what will motivate them to stop.

To explain, let’s take the example of owning a cheetah as a pet. This obsession results in around 300 young cheetahs being trafficked from the Horn of Africa every year, with only one in every six surviving the journey to reach the customer. Most are sent to the Arabian Peninsula where they are adopted by the super-wealthy and the consumers are almost exclusively men. While in recent years bans on purchasing wild animals as pets have been enacted in most countries in the region but they are poorly enforced and the trade continues.

Over the last couple of years, whenever possible I have sat down with the people who know these men either directly or indirectly. Everyone I have spoken to has, at one time, lived in the region providing the professional services Emirati families and the Middle East economy needs.

Under the agreement of anonymity, they confirmed that the consumer group for cheetahs was exclusively young(er) males who had limited status or power within their extended families. “Global media often explores gender inequality in the Middle East but doesn’t really mention the varying levels of male ranking” was one comment. These men also know they may never reach the upper echelons of the family. They have money, but they aren’t in a senior position; indeed, they may never play an important role in the family.

They get their status from their brothers, male cousins and male friends and they often buy an exotic pet on a whim because their brother or friend has one. “Their focus is to impress their male friends and relatives” said an observer, going on to say, “and they would tell lots of stories about male friends or relatives owning a big cat”.

Another person said “They would also attract attention with these animals wherever they went, and people would often ask them to take photos. They really liked this attention; they wanted to impress people and feel important”. Men (and women) with fragile egos and money can be very destructive.

Research tells us that there are only four human needs: Certainty, Variety, Significance and Connection and if we can’t fulfil these needs in a positive way we will fulfil them in a negative way, but we will fulfil them.

Image xavierarnau

Cheetah ownership aims to fulfil the Significance need but in a destructive way; the status anxiety of these men has major implications for the survival of cheetahs in the wild. All of this tells us that these young men must be given something that gives them status, but which isn’t a threat to the higher-status males of the family. In the past running the family’s philanthropic foundations and projects has been a way to give adult children status.

With much of the wildlife in the region on the verge of extinction, there are plenty of possible projects that would do ‘good’ and could be linked to status from contribution – Magnificence. These males could gain significance and leave a legacy by rehabilitating and rewilding parts of the region, something that would be remembered by future generations. There are precedents for this type of work, you just have to look at what the Tompkins Conservation is doing in South America and the work of The Maliangwe Trust in Zimbabwe.

Image WLDavies

Subscribe To

[mc4wp_form id=”29″]