Is Luxury Fashion Speaking With Forked Tongues?

Image alexandarilich

Lynn Johnson

10 August, 2020

Products made from python skin are some of the most profitable in the world. Every year global luxury brands make billions from python skin coats, trousers, boots, shoes, bags, belts and the list goes on.

Global luxury brands enlist influencers of all generations to drive up the desire for python skin products. And this desire is being pushed from the top, with Anna Wintour wardrobe choices showing she has no interest in the fact that there is currently no evidence of sustainable business practices in the fashion world for these products. But she is not alone, with everyone from Kate Moss, J-Lo, Rihanna and Celine Dion following Wintour into the pit.

The use of snake skins for the commercial production of leather only started in the mid-1920s, but by 1990 a regional review of supply-side countries in Asia found that python populations in several countries had already declined. The 1990 report discussed that collecting pythons for the skin trade had adversely affected populations and speculated that pythons likely remained ‘reasonably abundant’ in more remote areas not subject to intense collection pressure.

While the report admitted the population impact of harvesting skins could not be evaluated in detail, it did highlight some of the key loopholes in the monitoring system that could be exploited, and finished by saying a levy system should be investigated because there was evidence that the true value of skins was ‘substantially under-declared’.

Let’s step forward 30 years and sadly all the same problems remain, even though report after report has reaffirmed the conclusions of the 1990 research.

But it isn’t quite true that nothing has changed. In the intervening 30 years the world had seen mass deforestation, including in those countries that supply the python skin trade, such as Indonesia and Malaysia. There has been massive growth in the number of people who desire luxury products, with the fall of Communism in Eastern Europe in 1989 and economic growth in China and SE Asia. And we have had a technology evolution that could have easily solved the supply chain monitoring and transparency problems, but this technological development has been ignored by the companies profiting from and the regulators monitoring the legal trade in endangered species, including pythons. Luxury companies make billions from python skin products, yet they have been unwilling to invest the maybe $2-3 million needed to fix the supply chain for python skin.

I have to give credit to the regulators of the trade in endangered species, who always consider that the people at the early stages of the supply chain are often living in developing countries and in impoverished communities, so they work incredibly creatively to come up with something that works for everyone.

Image YevgeniyGq

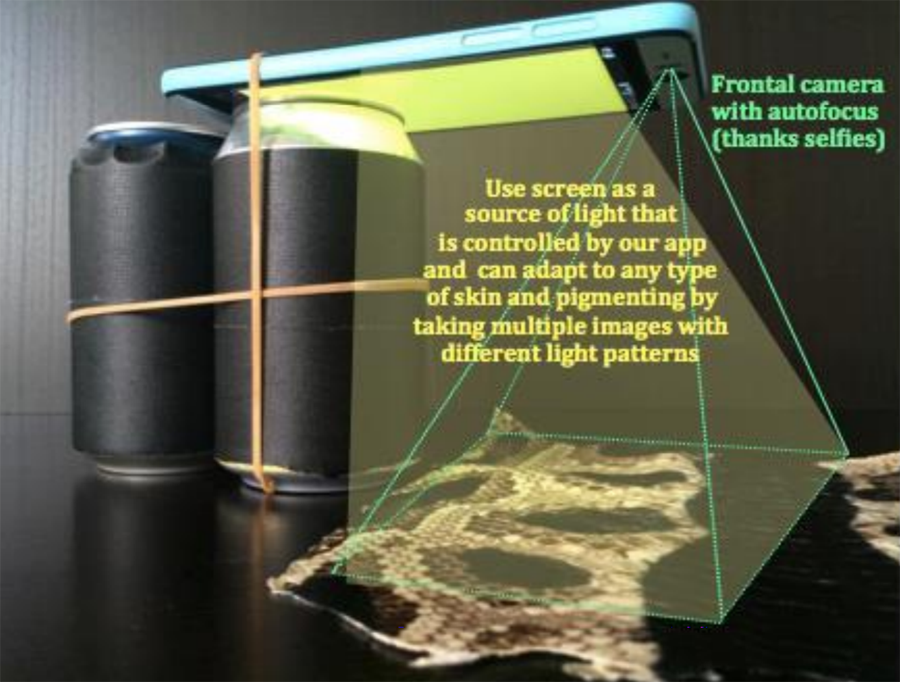

Just one example of this type of approach included the design of the so called The SodaCam Tripod System for tagging individual skins to help minimise laundering which was developed in 2015.

In fairness, I must acknowledge that the collaboration working on the SodaCam Tripod system included LVMH, Burberry, Giorgio Armani, the International Leather Bracelets Association (AQC) based in Switzerland, the Italian Tanners’ Association (UNIC) to name just a few.

So, what has happened? Has this system, that costs the price of 2 rubber bands, 2 used soda cans and a smart phone been rolled out? No, the SodaCam Tripod hasn’t been rolled out and neither have any of the other systems that have been considered over the last 20 years for tagging either individual skins or batches. Other than luxury companies and industries collaborating on countless studies and papers regarding traceability systems and processes, nothing has been implemented.

It remains comically easy to launder illegally harvested snakes into the legal supply chain of some of the richest companies in the world. This was highlighted by research published earlier this year which found between 2003 and 2013, luxury fashion brands had thousands of exotic leather goods seized by U.S. law enforcement; 5,607 individual items, nearly 70 percent of which were exotic leather products. Reptiles accounted for 84 percent of all items, many of which were belts, watch bands, wallets, shoes, and purses. According to the official seizure records Ralph Lauren accounted for 29% of the seized items, Gucci 16%, Michael Kors 10%, Jil Sander 6% and Coach 5%. Gucci had the highest number of individual seizure incidents—50—followed by Yves Saint Laurent at 41; other designers who has product seized included Diane von Furstenberg, Chanel, and Versace.

In response to the research Molly Morse, a spokesperson for LVMH, which owns a number of companies on the list—including Louis Vuitton, Marc Jacobs, Christian Dior, Givenchy, and Fendi—said in an email that the seizures connected to LVMH “were many years ago and generally related to paperwork and labelling processes.”. Well, it doesn’t matter that it was many years ago, given that the monitoring system hasn’t been improved since the 1970s when it was first launched.

For those who have been listening there has been a growing number of articles in the conservation press about forests being emptied. So maybe it is no surprise that I find myself writing this article in a second ‘Stage 3 Stay At Home Lockdown’. For two decades some of the world’s leading scientists have been expecting a pandemic of zoonotic origin like the coronavirus. They knew that humans are vulnerable because the line between us and exotic animals had long been breached as the natural world was exploited.

Has this prompted any action from the luxury fashion houses that use endangered wildlife in their products? On the 1st of July 2020 a media release from Kering stated:

“Today, for the first time, Kering has published a dedicated biodiversity strategy”

Frankly shouldn’t the company be embarrassed to admit that this is the first time it has published a dedicated biodiversity strategy, given how much money it has made from biodiversity over the years? But let’s not get too excited, the Avoid aspect of their strategy talks about “closely adhering to guidance issued under CITES, the IUCN Red List, and other relevant national and international conventions”.

A dedicated biodiversity strategy, but no new action. We probably should not be surprised. Kering and LVMH have always said they comply with CITES regulations – but those regulations don’t require traceability and rely on an obsolete monitoring system. Without traceability the illegal harvesting will continue. By setting an example on how to implement a 21st century traceability system for one of the most profitable trades in endangered species Kering and LVMH could demonstrate true commitment to preserving biodiversity and even help prevent the next pandemic. If live animals and derived products can be traced in real-time, it is much easier to control outbreaks

So what will it take to finally get action? We don’t need more scientific report or documentaries, the 2011 documentary by Karl Annan already showed in grim detail how the supply chain really works. Sadly this issue gets little press because the use of exotic and endangered species by the fashion industry falls into no man’s land between vegan fashion and pro-wildlife trade fashion and to many key fashion influencers don’t care.

And so the luxury businesses can just keep slithering along – unchecked.

Subscribe To

[mc4wp_form id=”29″]