Why ‘One’ Must Take A Risk

Image Robyn Charnley

Lynn Johnson

13 August, 2020

Prince Harry’s recent article in Fast Company spells out his and Meghan’s concerns about the online world’s ability to spread misinformation instead of truth, and to weaponise speech. In the article Harry goes on to say “advancements in technology and media have outgrown many of the antiquated guardrails that once ensured they were being designed and used appropriately”.

Many would agree with his statements that the digital landscape is unwell and that online platforms are contributing to a crisis of truth. What is interesting is that he and Meghan decided to use their celebrity in a very pragmatic way by calling companies and asking them to withhold their social media advertising dollars during July. In doing so, they highlight the only real way to get a sector or company to take notice of a problem and make changes is by reducing its profits, even if only for a month. When the leaders of companies aren’t intrinsically motivated to change there is little evidence that anything other than loss of revenue, brand or reputation will trigger transformation.

I applaud Meghan’s and Prince Harry’s willingness to have robust and difficult conversations with these business leaders. It is not the first time they have demonstrated a willingness to take risks. And while many may say that the couple takes these risks from a position of privilege and financial security, it must be pointed out that most other people in similarly secure positions don’t risk the chance of rejection by their prestigious networks and tribes. In the main, people’s concerns about loss of status within their peer group mean they keep their mouths shut and conform. With this very public stance the couple supported the Stop Hate For Profit campaign.

Harry voices his concern that we have all become ‘products’ of this digital space, which is very true. And the micro-targeting abilities of these platforms means we are susceptible to their coercive forces; as he says the cost is high.

But such toxic business behaviours and the resulting, tragic effects on the physical world are not exclusive to the digital landscape. And, while calling on business leaders, heads of major corporations, and chief marketing officers to ask them to withhold their advertising dollars for a month is commendable, asking these same business people to change toxic practices in their own companies would take the discussion to a whole new level; one I would like to think that Meghan and Harry have the tenacity to do. Could this courageous couple drive change in another industry that is not used to being questioned and doesn’t seem to have much capacity for self-reflection? Namely the luxury sector.

Last year the Duchess of Sussex was invited to be the guest editor of British Vogue’s September issue. While the cover featured 15 black-and-white photographs of women trailblazers, also interesting is that Meghan was invited to guest edit the most influential edition of the year for fashion magazines, which highlights her potential influence in the sector.

So here is a thought, if Meghan and Harry decide to use their power to contact company executives in the future I would like to nominate the luxury sector and specifically any company that uses endangered species in their supply chain.

This sector has used its deep pockets to ‘greenwash’ and misinform consumers about its efforts to ensure sustainability of everything from pythons, to stingrays to rosewood and more. Currently 34,500 endangered species are listed for trade restrictions by the global regulator, all of which can be legally traded.

As a species becomes rare, then sadly it becomes valuable. Some of the most endangered species in the world are legally traded in the most lucrative and exclusive industries.

According to Bain & Company’s Fall–Winter 2018 Luxury Goods Worldwide Market Study, the overall luxury market grew 5% in 2018, to US$1.42 trillion. Endangered species are used to add value to the luxury market through personal luxuries, including apparel, jewellery, beauty and wellbeing products. They are also used in architecture, high-end furniture and housewares, luxury hospitality, fine dining and gourmet food. This list is by no means exhaustive.

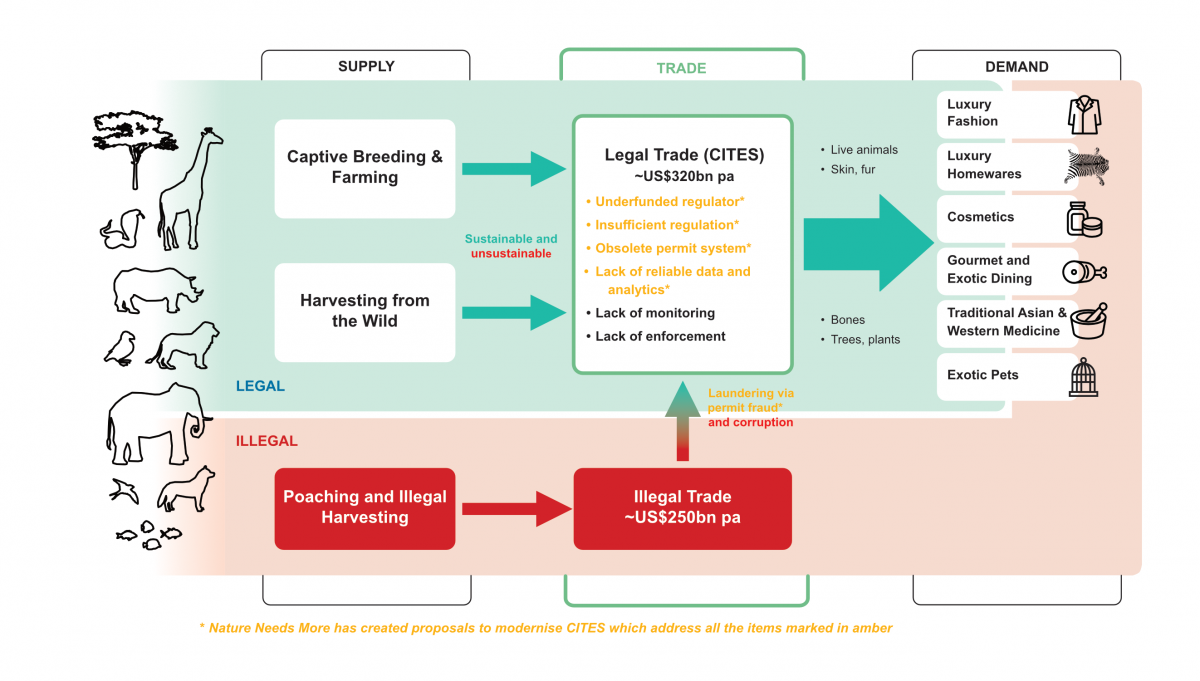

Just as in the digital space, the industry has outgrown its regulator, CITES, which still uses 1970s technology. Its annual funding of US$6.2 million to facilitate and monitor a legal trade in endangered species valued at US$320 billion, as long ago as 2009, in effect renders the regulation useless.

As Meghan and Prince Harry are thinking about who next to call, I would like to point them to research published in May 2020, investigating the sustainability practices of 80 luxury goods manufacturers listed on the New York Stock Exchange. For all 80 companies, the researchers found a grand total of only 289 announcements in the Wall Street Journal, between 1990 and 2019, regarding the implementation of sustainable practices. The trend was seen to rise over time, but the 168 announcements in the last decade (2010-2019) translate to 2 announcements per company per 10-year period!

While Prince Harry talks about radical justice in his Fast Company article, when it comes to the legal trade in endangered species, the first step is radical transparency, something that the luxury industry talks about but doesn’t do. The legal trade in endangered species is completely opaque, so it is easy for companies to highlight their ‘green’ or ‘sustainable’ credentials without having to provide any evidence to back up the claim and without any fear of anyone being able to prove them wrong. One transnational crime investigator we spoke to said that the CITES regulator hadn’t been modenised because the stakeholders wanted plausible deniability on the scale of the legal trade.

The luxury companies who use endangered species in their supply chains need to be questioned in the same way social media businesses are, because to quote Prince Harry, “there are billions of people right now—in the midst of a global pandemic that has taken hundreds of thousands of lives—who rely on information to make judgments about fact vs. fiction, about truth vs. lies. One could argue that access to accurate information is more important now than any other time in modern history.”

The accurate information is that this pandemic is zoonotic in nature. For two decades some of the world’s leading scientists have been expecting a pandemic. They knew that humans are vulnerable because the line between us and exotic animals had long been breached for direct exploration for the legal trade. If we don’t demand radical transparency on the legal trade in wildlife now, there will be another pandemic.

Could I suggest your first calls could be to LVMH and Kering Group.

Subscribe To

[mc4wp_form id=”29″]